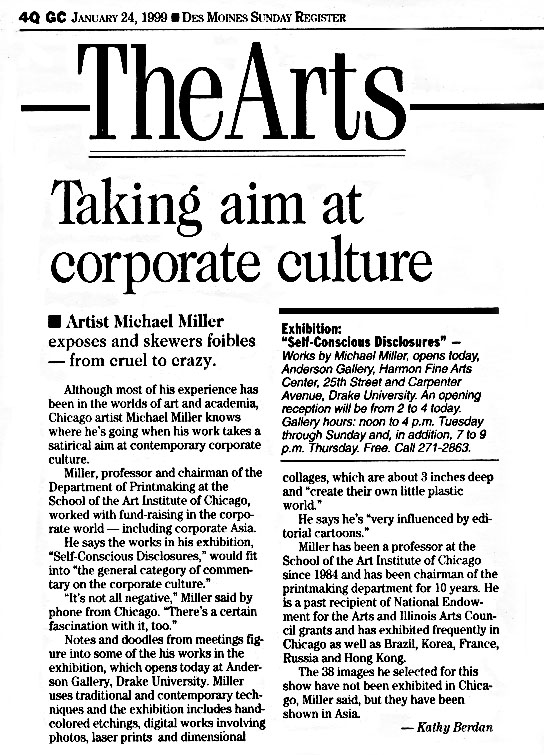

Review of Michael Miller's Artwork

Book Release/Signing, Quimby's Bookstore, Chicago, IL, 2006

(see Podcast Book Review of Nano: Stories in a Blink at http://www.badatsports.libsyn.com)

Art Letter (02/03/05)

by Paul Klein

Julia Walsh of Walsh Gallery consistently does a great job of presenting strong, challenging, thoughtful exhibitions. Anyone who is working as hard as I used to is making a significant effort. Julie goes back and forth between China frequently, creates thematically museum-worthy shows and keeps on moving. She’s got at least as many irons in the fire as I do and is perpetually conjuring up new visions. Not only that, she tears down the walls of her gallery for each exhibit and reconfigures it to fit the show. Her new show, which opens Friday is called Face to Face and was inspired by the art and travels of Michael Miller whose art I first showed about 20 years ago. Miller teaches printmaking and the School of the Art Institute and I doubt he ever unpacks his suitcase. He has an affinity for Asia and a fondness for Korea. Art provides a common language in his travels and while in Korea came across the exemplary and prolific linocuts of Won–Chul Jung. There are faces in Miller’s art and there are faces in Jung’s work, who reveals the beauty of the underbelly of faces in Korea; the faces of the “women of comfort” who comforted Japanese during WW II, but these are their faces today, some 60 years later. Or the faces of the white immigrants who are imported to do the dirty work. Julie Walsh does a great job. Her shows open our eyes to another world and to ourselves. I am moved every time I visit her gallery.

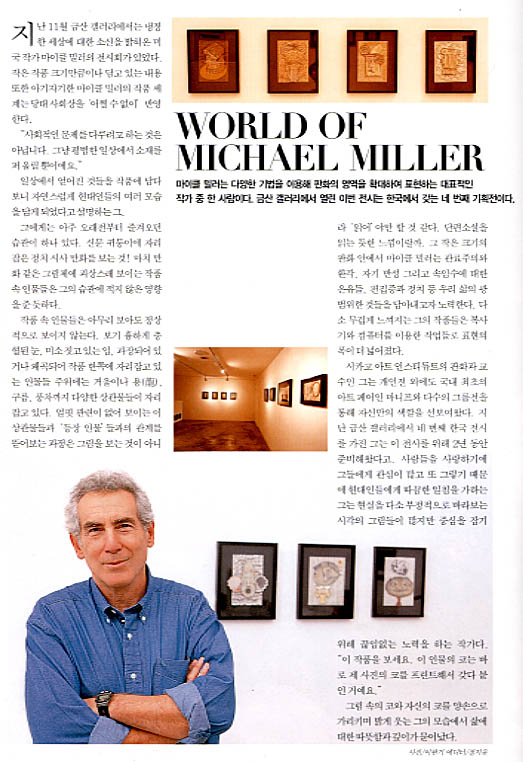

Review from Luxury

(Dec., 2001) from solo show at Keumsan Gallery, Seoul, Korea

Balance of Power

by Lenore Metrick, 1999

The archetypal story of corporate indifference and cruelty has been told and

retold often over the century. But it is rare to find the subject in fine

art, and rarer to see it become, as in the art works of Michael Miller, revealingly

transparent. With dry humor, Miller creates caustic, unsettling images that

take corporate structure and values to absurd degrees. The figures appear

caught in webs or are sandwiched between layers of resin, exposed like specimen

fixed in glass. Even more unsettling is Miller's blunt disclosure that the

narrative has become a familiar package. Employing standardized forms: a tie,

a maze -- so generic they function as abbreviations -- his work indicates

that the story has been told so often individual cases are no longer necessary.

Kirk Varnedoe pinpoints the appearance of caricature as an indignant response

to oppression to the early 19th century works of a print artist, the French

socialist, Philipon. And its characteristic function still prevails: "caricature

departs from appearances only to make the truth of life plainer, leaves the

world only to return to it." At the end of a century dominated by corporate

advances, Miller's art makes plainer what we even yet don't want to acknowledge:

that the story is no longer an expose, but is filled with platitudes. Even

though it still has the power to shock, business, meanwhile, has continued

as usual.

Miller's drawings makes us as familiar with disembodied ears, floating lips, and truncated ties, as with a harried, peevish, forlorn face which animates much of his work. Grotesque new life forms dominate his world, forms comprised of multiple ears, single eyes attached to a tie. In an eerie inversion, in some works the skyline of the city appears as an interior space. His elegant palette: buff tones, overlaid with shades of browns and blacks with a flash of red, or turquoise blue, bright green line running through, provides a counterpoint to his caricatured images. It comes as no surprise to learn that the model for the body parts was the artist. It is his ear, his nose, his lips that become disembodied and float ominously as the atmosphere in the shallow world. But, unmistakably, Miller has no interest in creating a self-portrait. In his art, the specific stands for the generic. Human figures function mainly as ciphers, with mask-like, non-individualized faces. In Balance of Power, 1998 inkjet print, two large ears attached to each other without bothering with an unnecessary head, are surmounted by a wide mouth, over which tilts an eye. This form dominates the foreground of the print; the background shows a diminutive circle of the earth in a field of sky and clouds. In Miller's world only essential organs form the figure, superfluous limbs are discarded, no place for them, nor need. Here the inanimate and the partial are elevated to the level of the human. But this yields dubious results. When the insentient and the human attain equality, the former becomes elevated, but the human risks being reduced. And this equation, this double equation carries Miller's punch, the force that unsettles the viewer.

In his art the structure of the object intensifies the meaning. Miller exploits the constraints of the flat print and of the shallow box -- he flaunts their limitations. He uses structure to magnify attributes coinciding with corporate preferences and exclude all others. For instance, he manipulates the shallow space to amplify the claustrophobic atmosphere of his subject. Then, perceiving that the corporate world rewards the team player over the individual, Miller zealously follows suit, creating an extravagant world inhabited by a single, often repeated, caricature and generic body parts. This, in turn, conforms to another corporate bias against emotions, since it effectively eliminates personal narrative or experience. By boxing the narrative, form and function seem eager to harmonize in fabricating a world devoid of individuality, where emotion seems frozen.

Clearly, these images are not idle musings of a bystander, but result from the brooding of an insider. The artist began this series of works as sketches in meetings. In 1992 after years as an artist and academic for the first time he became involved in administration, his presence required at board meetings. A novice, he observed the dynamics with fresh eyes. But a lifetime of experience gave him a unique perspective: he indeed had fresh eyes but he had an experienced brain. Rather than believe this structure to be the only way possible, he was aware of alternatives and could imagine other possibilities. He wanted his art to depict the perniciousness of the system without abandoning the viewer to a completely negative vision. The ubiquitous coiling figure in his work, although precariously balanced, is always perched on a solid cone of earth.

Miller's caricatures function as pawns, innocents literally caught in the web of a world they had not created, not even imagined. Curiously his world finds a precedent not as much in visual art as in literature, resembling the world described in Voltaire's Candide. In Miller's world, too, the protagonists continually encounter cruelty, greed, deception, every imaginable vice, challenging viewers to confront their world, account for the distortions.

Printmaking has characteristically been associated with democratic dissemination of images and with images of popular culture. To this day, printmaking retains an affiliation with the viewpoint of the underdog rather than the elites. Not surprisingly, then, Miller credits 19th-century iconoclast printmaker Honoré Daumier as a major influence. Daumier initiated much that we now recognize as modern in art: eliding categories of high and low art forms, elevating caricature, expanding the locale of the mundane from humor to tragedy. Miller's work emulates the spirit of this work. In Art and Illusion, Gombrich states that "In and with Daumier the tradition of physiognomic experiment began to be emancipated from that of humour. Very early in his career Baudelaire had noticed that his lawyers, judges, or fauns are far from humorous. They are creations in their own right, often terrifying in their intensity, masks of the human passions which probe deeply into the secret of expression."

With a comprehensive knowledge of print history and traditional techniques, Miller works at the forefront of print technology. He replicates the tradition process of layering images, but the layers in his works are often in three dimensions. Using a laser printer, Miller constructs images that he then embeds in various layers in a 4-inch deep matrix of plastic resin, forming clear brick-shaped works of art. Each piece involves organizing separate layers and orchestrating their interactions, both physical and thematic. Miller meticulously cuts out sections of images in the upper levels to allow the viewer to see the images at each level simultaneously. All his three-dimensional resin pieces share basic ideas. As Miller described it: "The story of one is the story of all." He often revisits an idea, changing it to increase its meaning.

Human Cost typifies the construction and the ideas. It consists of five layers of images embedded in a clear resin. The resin was poured into an 8 x 10-inch wooden form embedding the lowest layer of depiction -- a laser printing of faded lines. Then more resin was poured up to the level desired for the second layer and a second depiction embedded: a blue grid with evenly spaced cut out areas. Then more resin and the next layer - a printing of an ear. The fourth layer: an outline, a cartoon face. When viewed straight on the face overlaps the ear in the layer below while allowing glimpses of the grid in lower layers. And then the uppermost layer: a hoop or red circle cut out and two minuscule shapes of people, one in black the other in blue, tiny at the peak of the hoop. This too is covered by a layer of resin. Every layer of images corresponds to a different perception of reality. The lower level markings are fundamental, rudimentary markings prior to representation. The cubicles and mazes in thesecond layer insert a system of regularity -- circuits, repetition. And there is often something which becomes embedded, seems to get stuck in the matrix. This is found in the third layer. The fourth layer introduces a character, the cartoon-like 'schlub': a working stiff, someone more caught in the system than playing with the system. And the fifth layer is the figures walking together on a loop, perpetual motion. The artist originated the piece as a concrete representation, tongue in cheek, of the adage the walls have ears but he quickly moved beyond this, conveying an atmosphere of paranoia and a maze of relationships.

Miller has been startled at our culture's persistence in mistaking photographic realism for reality -- emotionally if not consciously. To avoid this he manipulates photographic images, or removes them from a realistic context. A surface, although transparent, always intrudes between the viewer and the images. The artwork is constructed so that the viewer looks through the surface and at the surface at the same time. In this way, although Millers art confronts issues of art and reality, he avoids leading the viewer to confuse image for actuality. This directs focus onto ideas, not appearances. Conspicuously artificial and unsentimental, (again recalling Voltaire's writing) Miller's art allows a dispassionate examination not possible with graphic realism. The bloodless violence in his art can support an unflinchingly view: no bones break, no bodies bleed. But nevertheless through these surreal images Miller exposes a place of nightmare, its harshness reflecting on the system it models.

Some of his works depart even further from a narrative structure, the images becoming emblematic. They directly examine issues implied within the other works: the weight of the goal, the question whether means justify ends, the ever-present comparison with an unattained and unattainable ideal and the undercurrent of a ceaseless lament. Less than Ideal, an Iris print from 1998, is disarmingly because it seems a simple comparison but it consolidates a complex of thought. (And many artists have reflected upon how much precedes an idea before it can be portrayed so succinctly.) Here two profiles are placed side by side. One is an Egyptian ideal, familiar from art history, mask-like in its smooth perfection, straight nose, balanced features. The other profile, presumably based on the artist's, is thicker, the nose wider, the skin more broken and pocked marked. The initial impulse is to read this dolefully, as an accusation against the real, the failure of life to live up to art's standards of perfection. But at the same time, both profiles now are equally unreal, both now are art. Using one profile to comment on the other raises questions about beauty: integrity and ideal, illusion and realism. They uncover our attempts at self representation, our uneasy relationship with time and aging. What began with a simple comparison becomes more ambiguous and problematic.

Another print from the same year elaborates this path of scrutiny. Relic with ears depicts a photographic profile view of a nose -- a slice of realism -- surrounded by ears, eight of them, all hand drawn. An opposition is set up, creating a tension between the body fragments, an impression of survival. These isolated fragments heighten the emphasis on sensory function as well as portray all that remains. The relic is not with a visible ideal, yet continues to wrestle with standards not portrayed but implicit.

Many forms of modern

anxiety appear in Millers works but underscoring them is the fundamental struggle

for primacy in self-definition. The desire for autonomy in self definition

is constantly subverted. Alternative ways of viewing our own lives come from

the corporate hierarchy, or from instituted ideals, or from a multiplicity

of ways of being in the world, seductive and confusing. Miller represents

these tensions. His humor draws the viewer into an extravagant world, absurd

and preposterous, which poses unanswered questions. Miller likens his work

to a cymbal crash: the small images hit and dissipate slowly, lingering in

memory.

Lenore Metrick is an independent art critic. She has written art reviews for the Des Moines Register for two years, as well as articles for Public Art Review, Dialogue magazine, among others. She has taught art history at several universities, including the University of Indiana and Northeastern Illinois and taught in the University of Chicago's Basic Program. She has served on art juries and panels, most recently at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Currently she writes art criticism on an independent basis and lectures at the Des Moines Art Center.

Review

of Michael Miller's Artwork

by

Corey Postiglione

Michael Miller creates

powerful socio-political images that are not didactic or preachy. Irony and

whimsy abound in these elaborately designed, beautiful crafted works. The

main focus of Miller's work is in the corporate culture with all its attendant

foibles, its predatory savagery and its capacity for craziness rendered in

the grand tradition of such graphic satirists as Honore Daumier, Georg Grosz,

Posada, and even the “bad boy” of the 1960s, R. Crumb. References to pop culture

-- editorial cartoons, comic strip imagery, tattoo art -- are intentional:

“I try

to create work that would be equally at home on a gallery wall or in the newspaper,”

says Miller.

For this exhibition, Miller has assembled a group of multimedia work that he has developed over the last three years. They form a lexicon of images that weave a kind of narrative (albeit without the traditional conventions of plot and document) with a recurring cast of characters that range from the frantic Spinning Man to the forlorn image of Worried Man. However, to soften this dark tableau, Miller imbues his visuals with sardonic humor and a fantastic dreamlike mise-en-scene.

Miller's extensive range of subject matter is matched by his formal command of contemporary print media technology. In an attempt to bring printmaking into accord with the innovations of image production witnessed in the latter part of this century, he has evolved a complex process for the development of his final works. He begins with drawings (or doodles as he sometimes refers to them) or photographs that are that are then transformed through the use of copier and computer resources; the additional use of working collages and an occasional appropriated image (in one case a cloud motif from a Durer print) prepare a work for its final incarnation as a print or dimensional collage. Some of the finished prints are hand colored to give them even more visual richness. The resultant group of images is a wonderful amalgam of thoughtful commentary coupled with an extraordinary craft that is both aesthetically satisfying and intellectually challenging.

Corey Postiglione

is an artist and writer who currently teaches Art History

and Critical Theory at Columbia College Chicago.