Fingering Photography:

Index and Digit

(an excerpt)

by James Hugunin

Lace

(1844) William Henry Fox Talbot

and

Classical

Profile, enlarged digital image

Joseph Squier, computer artist and assistant professor of Art and Design at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign gave a lecture at Purdue University, "Art, Community, and the Colonization of the Internet" (1994), wherein he remarked, "I have not felt a need to distance myself from other art practice, or separate myself from other artists. But rather a need to maintain, and in fact cultivate, a sense of solidarity with both my contemporaries and those artists who have come before me." Mr. Squier went on to suggest we not reject the past, but reflect on it and learn from it. Although he was not blind to the fact that the computer presents us with a new tool capable of dramatically new potential for aesthetic production and distribution, he also noted that we must "resist being blinded by our infatuation with the means and the tools, and not lose sight of the end."

Invention

of Drawing (1830)

by

Karl Friedrich Schinkel

I shall continue in Mr. Squier's spirit of making connections between past and present and his caution toward unreasonably glorifying or condemning this new tool. I shall argue a continuity of ends, without denying they are markedly different means, between past photographic practice and what some term "post-photography," the enhancement or creation of photographic imagery via digital computer technology. In a 1985 article "Zone V: Photojournalism, Ethics, and the Electronic Age," journalism professor Howard Bossen argued against this position, claiming that given the capacity to digitally delude we are now confronted with new ethical questions in photography: "Computers can be used to create images that never existed in the real world but are visually indistinguishable from conventional photographs made of the real world, . . ." The digital manipulator, Bossen argued, may conjure up something that wasn't there in actuality, for instance, the fanciful completion of an earlier scheme of Palladio's Villa Pisani via computer manipulation. Or the manipulator may make something disappear from where it once existed, as in the seamless Removal of John Howard's Statue from Harvard Yard demonstrates. Gary Hesse, Assistant Director of Light Work, agrees, worrying that, "Becoming more dependent on digital information and stimuli, our collective experiences will fall prey to the ease with which digital information can be distorted and manipulated."

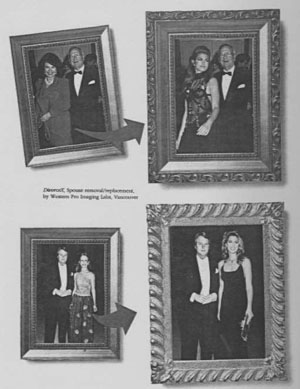

DivorceX (Spouse removal/replacement) by

Western Pro Imaging Labs, VancouverYet such excision is hardly a new capability. It had already been accomplished in conventional photography, albeit less easily and seamlessly. For instance, in the Soviet attempt to rewrite history the figure of Trotsky, standing below on the right in a photograph of Lenin Addressing a Crowd, is neatly excised.

Selective Removal of Trotsky from a photograph of

Lenin addressing a crowd on May 5, 1920, non-

computer manipulation used to achieve the effect

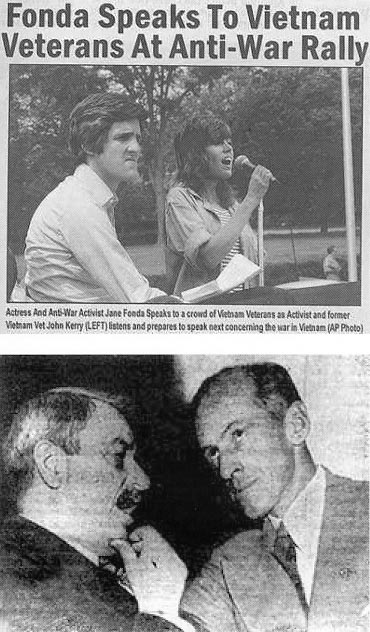

Digital

Composite: John Kerry falsely shown with Jane Fonda

in a 2004 composite (top); Photo-composite: Maryland senator Millard Tydings

similarly depicted in 1950 with Earl Browder, former head of the U.S. Communit

Party

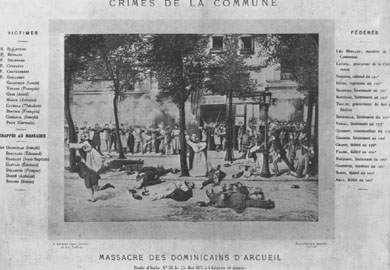

And, interestingly, in Leon Trotsky's History of the Russian Revolution publishing houses have repeatedly used as a factual illustration of the 1917 October Revolution a still frame excised and enlarged from Sergei Eisenstein's 1920 filmic recreation of the event in October — no one seems to have found this "pernicious." Certainly, the computer, a new tool, has permitted a more efficient accomplishment of such deletion. But such desire has plagued conventional photographers ever since they realized photography willy-nilly captured everything before their lens whether they wanted it there or not, promoting the compensatory use of retouching, air-brushing, and more overtly manipulatable non-silver processes such as cyanotype, bromoil, and gum bichromate printing. Conversely, photography has suffered from not being able to always capture what it hoped it could. So addition — via photomontage, as opposed to excision — was employed; for instance, Eugène Appert's 1870 "documentary" photograph Crimes de la Commune: Massacre des Dominicans D'Arcueil, Route d'Italia No. 38, 25 Mai 1871, à 4 heures et demie — issued by the Thiers government to justify, in turn, its massacre of the Communards two months later — uses such fakery to record purported violence against the clergy during the revolutionary upsurge by the Paris Communards. Yet, it is as if the image in itself was insufficient testimony. Appert flanked the image with extensive printed verbal accompaniment to enhance the truth-effect of his composite, anchoring the after-the-event fakery to the list of victims and perpetrators framed by a lengthy denotative title specifying precise locale, time, and date of the event. Although seemingly a documentary image, it was produced after the alleged event, the montage serving to conger up what was supposed to have occurred. That is, people were probably fooled by this image only to the extent they wanted to be misled due to their hatred or misgivings about the Commune, because the photographic technology of the day was too bulky for such a spot news shot and the faster emulsion gelatin dry plates were still not available to arrest action as depicted in Appert's image.

Massacre

of the Arcueil Dominicans, May 25, 1871

(falsified

reportage, albumen print) Eugene Appert

Concerning the implications of this image, photo historian Naomi Rosenblum writes:

- "Though

not the first time that photographs had been doctored, the acknowledgment

that documentary images could be altered marked the end of an era that

had believed that such photographs might be pardoned anything because of

their redeeming merit—truth".

- "The

visual is neither the double nor the outrageous, false or inaccurate misrepresentation

of something else; the visual is something else, something which is not

neutral, which has its own laws, effects and exigencies."

"Let us designate as 'photological' that obstinate will to confuse vision and cognition [connaissance], making the latter the compensation of the former and the former the guarantee of the latter, seeing in directness of vision the model of cognition."

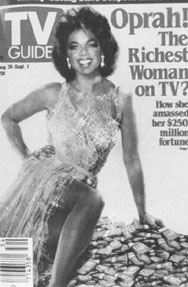

Oprah

Winfrey's head/Ann-Margret's

Body

on the Cover of TV Guide

The digital manipulator can produce fancies similar to Appert's. He or she can play mad-scientist, substituting one identity for another as seen in TV Guide's cover of Oprah Winfrey's head on Ann-Margret's body. Nevertheless, an 1890s photograph of Toulouse Lautrec paints Toulouse Lautrec by Maurice Guibert, a photographic substitution of the same identity twice, is in its seamlessness every bit as visually convincing as Oprah's new body.

Toulouse

Lautrec Painting

Toulouse

Lautrec, Mauric Guibert

In both instances,

however, we are again not really fooled as to the existence of two Lautrec's,

or of the ultra-glamorous Oprah. We can finger the trick for historically

we know Lautrec had neither twin brother nor some strange Döppelganger

dogging him; and, we know from Oprah's daily television appearances her body's

substantial build. The charm of Lautrec Paints Lautrec resides in it figuring

our sense of ourselves as psychologically "split subjects," an invisible condition

brought to visibility by this trick photo. More pernicious is the image of

the slimmer Oprah. Its sexism is not dependent upon the viewer actually believing

that Oprah really is slimmer; the image's function is, in fact, intensified

by our knowing it isn't "real." The viewer knows Oprah isn't that slim (a

lack) and, by implication, that "I'm not so slim either" (another lack), which

is promptly followed by the internalized societal accusation: "You should

be slimmer." Society's desire now becomes our viewer's desire: "I want to

be slimmer." The cover image, without tricking our viewer into believing Oprah

is really so thin, yet re-enforces our viewer's insecurities, stimulates desires

(rooted in lack), and naturalizes the patriarchal stereotype of the slim sexy

body. Our viewer has unwittingly become an accomplice in the production of

meaning. The viewer is caught up in a world of images — what French psychoanalyst

Jacques Lacan would "the Imaginary" — and so fails to recognize "the Real"

(what Lacan terms "misrecognition). Thus the great force of the photographic

— and this is confirmed in these of Lautrec and Oprah—is not its supposed

transparency and its optico-chemical contiguity to the real, but rather its

anchorage in the obsessional: the true referent of the image is not the real

per se, but the Imaginary. This produces of the reality effect of the image.

. . .

If

Groucho and Rambo had been

at

Yalta, computer manipulation