U-turn

presents a project that extends my research in

the representation of prisoners. In 1988 I began a review of Morrie Camhi's

The Prison Experience (1988). It seemed provocative to contrast that

photobook with Danny Lyon's classical documentary Conversations with the

Dead (1971), to observe that Camhi's book was "postmodernist"

in its approach to the topic, while Lyon's was "modernist." What

was supposed to be a five-page review turned into a 30-page chapter of what

was to become, five-years later, a book-length study of the photographic representation

of prisoners (A Survey of the Representation of Prisoners in the United

States: Discipline and Photographs, The Prison Experience (Edwin Mellen

Press, NY, 1999). So much material was "out there," so many recent

photographic forays into the topic, that I felt obliged to extend the book's

theme into covering more recent work by artists involved with any aspect of

the carceral. "Pointing to Prisoners" is the result. I see this

project as being continually open to new contributions, so I encourage

readers to submit their visual or written work to enhance this project (make

inquiries via e-mail: Jim@uturn.org).

U-turn

presents a project that extends my research in

the representation of prisoners. In 1988 I began a review of Morrie Camhi's

The Prison Experience (1988). It seemed provocative to contrast that

photobook with Danny Lyon's classical documentary Conversations with the

Dead (1971), to observe that Camhi's book was "postmodernist"

in its approach to the topic, while Lyon's was "modernist." What

was supposed to be a five-page review turned into a 30-page chapter of what

was to become, five-years later, a book-length study of the photographic representation

of prisoners (A Survey of the Representation of Prisoners in the United

States: Discipline and Photographs, The Prison Experience (Edwin Mellen

Press, NY, 1999). So much material was "out there," so many recent

photographic forays into the topic, that I felt obliged to extend the book's

theme into covering more recent work by artists involved with any aspect of

the carceral. "Pointing to Prisoners" is the result. I see this

project as being continually open to new contributions, so I encourage

readers to submit their visual or written work to enhance this project (make

inquiries via e-mail: Jim@uturn.org).

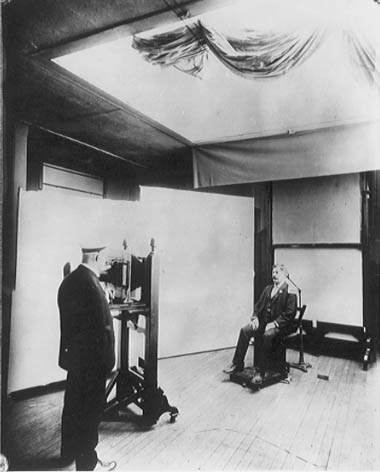

Mugshot procedure, Joliet Prison (c. 1890s)

courtesy of Chicago Historical Society archives.

In chapter eight of my book I wrote:

As we approach the year 2000, the communitarian spirit of the 1960s — the belief in social "holism," what theologian Paul Tillich termed "beside-each-otherness"— is fast eroding. We increasingly narrow the scope of those we trust and care for. This is a social "atomism" that is manifested in our indifference to the impoverished, our lack of concern for those who end up in prison largely due to their educational and economic deprivation, and our bitter cries for eye-for-an-eye revenge via the death penalty. This is an "against-each-otherness" — expressed even in our "road rage" at those unfortunate enough to get in our harried way while driving — a rapidly increasing form of violence that has resulted in murderous assault that, in turn, may put the perpetrator on death row where he or she will be killed by the state. A circular pattern of indifference feeding violence feeding indifference feeding violence. Need I ask whose political and economic interests this social atomism and wheel of misfortune serves?

It is against this background that increasingly politicians, sociologists, as well as artists and scholars have been focusing upon the problem of the prisons. I have gathered here work by Gary Dobry, Deborah Luster, Todd Margolis, Robert Neese, Stacey Martin, Louise Noguchi, Angelo, Mary Patten, Margaret Stratton, and myself.

Murder is not generally a subject in which most artists find themselves immersed. But twelve years ago, Deborah Luster's mother was murdered, sparking a photographic project which led her to three different state penitentiaries in Louisiana, her home state, as a means of healing and understanding.

Speaking of murder, Gary Dobry's writing, "Murdering Christ (and the Death Penalty in USA Y2K)," pleads: Every time a self-proclaimed Christain advocates murder of the poor and "meek" in America for their crimes against society, I feel the jaundice stare of Judas and his kiss of death. In his irreverant second article, "Murder and the Intellectuals," Dobry takes a swipe at the gullible intellectual by taking by comparing Sartre's championing of Genet to Mailer's lionizing of Jack Henry Abbott, reminding us that some "cons" do "con." Writes Dobry:

What Abbott needed was an "intellectual"! Abbott needed someone to "meddle" outside their own "area of expertise," like Sartre did with Genet to get Abbott out of prison. It was Abbott who started writing to Mailer, and it was Mailer, Mailer the intellectual, that was conned by Abbott. There's a reason they're called "cons" you know. But, there is also a reason guys like Mailer are called "intellectuals" too! The guy off the street would've been too hip to fall for Abbott's game, but not an intellectual! Abbott, in my opinion, knew exactly who he was writing and for what reason: to get out of prison!

Todd Margolis is represented by an online Flash animation that introduces his still in-progress interactive VR carceral environment, Lockup, at The Cave, University of Illinois, Chicago.

Stacy Martin's curiosity, wonder and yearning for something different lead her to a deliberate and conscious choice to find empathic approaches using art therapy in a correctional facility. Her thesis concentrates on the process in which empathy is attainable in a challenging environment.

The artistic process of Louise Noguchi's recent work, the Compilation Portraits, involves having herself photographed professionally in the same pose as her chosen criminal or victim and then blowing up both images. She cuts these photographs into strips and weaves the warp of her own image into the woof of the blown-up images of the police photo.

Angela Grossman's canvases, enhanced and manipulated mugshot photos, strips the subject of any specific identity, its carceral context, as well as the crime as she works to disguise these subects and protect their family privacy. Then she takes the image of the convict's face, and gives it a body; completes it. She sometimes renders these convicts as naked, adding to their vulnerability.

Chicago artist Marc Fischer, writing of inmate-artist Angelo, confesses aftering curating a show of his work: "I try to think of Angelo first as a fellow artist and a friend, but he is also an inmate in the California Prison System. The fact of his incarceration is impossible to forget. It is embedded in the form of his drawings and the meager supplies that he uses to make them. It announces itself in an official ink stamp on every letter and envelope of pictures that he sends. Angelo is 56 years old. He has been in prison for the past ten years. His tentative parole date is 2008."

Robert Neese's Prison Exposures (1959) is an inmate-photographer's "take" on life inside Iowa's State Prison at Fort Madison, along the Mississippi River. Placating the prison authorities, Neese pits the older, more mature inmates who are reformable against the younger "hard-rocks" who appear to be much less rehabilitatable. My article on his book focuses on how Neese's narrative constructs a set of binary oppositions that reframe the inmates in ways that are more coincident from the dominant repressive modes of representing prisoners.

Letter to a missing woman (color, 4 minutes, 1999) by Mary Patten combines documentary "truth" and fiction in a "crazy letter" to a "missing woman" -- based partly on memories of someone who has been a fugitive for 17 years, and partly on an imaginative reconstruction, through an examination of public documents and private history. The"letter" is a kind of one-sided conversation across the space of many years, a futile attempt to bridge two wildly divergent paths. Here short excerpts from her tape accompany stills from this tape.

The work of Margaret Stratton straddles several genres: it is at once photography, social documentary, and a political commentary concerning out most politically- charged contemporary issue: the institutionalization of incarceration. The prisons represented here are from Eastern State Penitentiary (not depicted are images from Jamesville Penitentiary, Montana Territorial Prison, and EIllis Island) which no longer function as prisons. They are, she says, "alternatively, gothic ruins, film and photography sets, State and National Parks, museums, tourist attractions, historic sites and condemned structures riddled with toxins. Their relevance to society and their existence as metaphors are intertwined with the ambivalence and confusion that characterizes public opinion about punishment and captivity."

The diversity of approaches seen here is characteristic of the range of material attempting to address this complex topic. I this project keeps expanding and more and more contributions will be submitted to enrich our presentation.