Theory:

Mauss's most influential work is his Essay sur le don (1925; English translation:

The Gift: Forms and functions of exchange in archaic societies, 1954),

a comparative essay on gift-giving and exchange in "primitive" societies.

On the basis of empirical examples from a wide range of societies, Mauss describes

the obligations attendent on gift-giving:

the obligation to give gifts (giving, or potlatch, shows oneself as generous,

and thus as deserving of respect), the obligation to receive them (by receiving

the gift, one shows respect to the giver, and concommittantly proves one's own

generosity), and the obligation to return the gift (thus demonstrating that one's

honor is -- at least -- equivalent to that of the original giver). Gift-giving

is thus steeped in morality, and by giving, receiving and returning gifts, a moral

bond between the persons exchanging gifts is established.

The

significance and nature of gifting in Northwest Coast potlatches has varied through

time and across cultures. It is commonly portrayed as extremely competitive, with

hosts bankrupting themselves to outdo their rivals and aggressively destroying

property. While this form of gifting characterized practices of northern groups

such as the Kwakiutl, such competition would have been considered inappropriate

during Nuu-chah-nulth or Salish potlatches on the southern coast. Potlatches are

to be distinguished from feasts in that guests are invited to a potlatch to share

food and receive gifts or payment.

Items

lined up for a potlatch, Victoria, British Columbia, 1865mmPotlatch

figure welcoming guests

Potlatch

[Chinook jargon, from Nootka, patshatl: giving], a ceremonial feast of

the Indians of the Northwest coast marked

by the host's lavish distribution

of gifts requiring reciprocation (Source: Webster's Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary).

Mauss

stresses the idea that twentieth-century Western society, although obliged to

adopt new principles in order to move forward, would also do well to come back

to certain earlier principles, and in particular to the practice of "noble

expenditures." As regards earlier societies's gifts and expenditures,

they did not entail, writes Mauss, "the cold reasoning of the merchant, the

banker and the capitalist." For Mauss, the subjective gift is the opposite

of market relations, but it still bears their stigmata. For, in the imaginary

of individuals and groups, it appears a bit as the dreamed of other side, as the

inverted dream of the relations of power, interest, manipulation, and submission

involved in commercial relations and the quest for profit, on the one hand, and

in political relations and the conquest and exercise of power, on the other. When

idealized, the uncalculating gift operates in the imaginary as the last refuge

of a solidarity, of an open-handedness which is supposed to have characterized

other eras in the evolution of humankind. Gift-giving becomes the bearer of a

utopia, a utopia which can be projected into the past as well as into the future.

It

is the cardinal difference between gift and commodity exchange

that a gift

establishes a feeling-bond between two people, while

the sale of a commodity

leaves no necessary connection.

--

Lewis Hyde, The Gift: Imagination and the Erotic Life of Property

Only

economism, Bourdieu argues, with its 'restricted defintion of eco-

nomic interest which is the historical product of capitalism,' demotes

the symbolic to irrational sentiment or passion. By measuring all activity

against the 'unambiguous standard of omnetary profit, the most sacred

activities are also constituted negatively as symbolic,

that is with the

connotations often carried by this as devoid of concrete material effect,

in a word, gratuitous, in the sense of disinterested but also

useless.

-- Michele

H. Richman, Reading Georges Bataille: Beyond The Gift

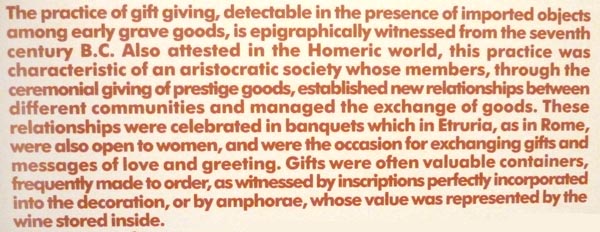

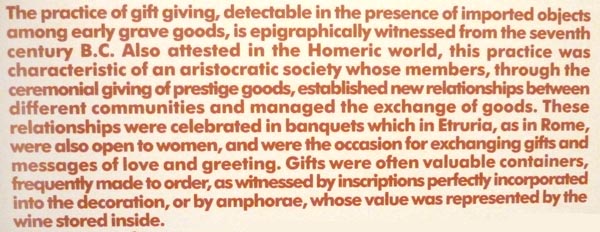

Gifting

in the ancient world: a Gifting Container displayed in a Museum in Rome.

Gifting

is an essential aspect of the "Burning Man" festival held yearly in

the Black Desert of Nevada (click on images)

:

Some

of the most interesting scholars in France today

you never hear about at all. One such is a group of intellectuals who go by the

rather unwieldy name of Mouvement Anti-Utilitariste dans les Sciences Sociales,

or M.A.U.S.S., and who have dedicated themselves to a systematic attack

on the philosophical underpinnings of economic theory. The group take their inspiration

from the great early-20th century French sociologist Marcel Mauss, whose most

famous work, The Gift (1925), was perhaps the most magnificent refutation

of the assumptions behind economic theory ever written. At a time when "the

free market" is being rammed down everyone's throat as both a natural and

inevitable product of human nature, Mauss's work -- which demonstrated not only

that most non-Western societies did not work on anything resembling market principles,

but that neither do most modern Westerners -- is more relevant than ever. La

Revue du M.A.U.S.S. was launched in 1981 by a handful of French academics

working in sociology, economics or anthropology. They resented the path which

was being imposed to social sciences at the time, notably their submission to

an omnipotent economic model. They disagreed with an exclusively instrumental

vision of democracy and social relationships.While Francophile American scholars

seem unable to come up with much of anything to say about the rise of global neoliberalism,

the M.A.U.S.S. group is attacking its very foundations.

I'll

tell you a plan for gaining wealth,

mBetter than

banking, trade or leases --

Take a bank note and fold it up,

mAnd

then you will find your money in creases!

This wonderful plan, without

danger or loss,

mKeeps your cash in your hands,

where nothing can trouble it;

And every time that you fold it across,

m'This

as plain as the light of the day that you double it!

--

"Epigram for Wall Street," Edgar Allan Poe (1845)

Bibliography:

- Unemployed D.C. man giving money away to strangers to

help foster kindness by Susan Kinzie Washington Post Staff Writer

Friday, March 19, 2010

The guy behind the meat counter is looking at Reed Sandridge

kind of strangely. Giving away $10 every day to a stranger -- an idea Sandridge

had soon after he was laid off from his job at a Washington nonprofit group

last fall -- isn't as easy as it sounds. A ten-spot in his heart for strangers

If you were to receive $10 from a stranger, what would you do with it? Carlos

Canales, a 28-year-old butcher at Eastern Market, is hesitant to take the

money. "What do I have to do?" he asks. No strings, no hook. Sandridge,

36, a businessman-turned-shoe-leather philanthropist, just wants to help.

His mom, the daughter of a coal miner whom he remembers most for her kindness,

always told him that when you're going through tough times, that's when you

most need to give back.

So not long after he was laid off, on the third anniversary

of his mom's death, he started his "year of giving," documenting

each $10 gift in a small black notebook and then blogging about the people

he meets. By Day 94, he had given away almost $1,000, handing out money in

blizzards, in rainstorms, on the sunniest of days. He gave $10 to a guy playing

the trumpet outside Verizon Center, the president of a brewery, someone dressed

up as the Statue of Liberty, a hard-drinking PhD, a man who held up a basketball

to block helicopters overhead from eavesdropping on their conversation, the

curator of a small museum and a whole lot of homeless people.

Sandridge, who is outgoing and has a ready grin, and, sometimes,

a brown scruff of almost-beard, knows $10 is precious little, even to the

most down-and-out. It feels significant only when the daily donations are

subtracted from his shrinking bank account. He's been using his savings and

a few hundred a week in unemployment benefits to pay the mortgage on his home

in Dupont Circle. But he hopes he will network his way to a salary again long

before he runs out of cash.

But the year of giving is not about the money. Sandridge

is trying to spread an idea. Doing nice things all the time is addictive,

he said. Besides, he added, "being unemployed, I was starting to go nuts."

He wanders the city looking for strangers who appear as if they might need

help or have an interesting story to tell. He has a few rules: He gives only

$10, and he doesn't take anything in exchange. He's getting better at it.

The first three times he tried, people refused, suspicious, and walked away.

Now, he easily persuades people to take his money -- even Canales, after a

few moments, accepts the $10 bill -- and to tell him what they're going to

do with the unexpected gift. Every once in a while, he knows the money really

helps someone. It pays for a meal or turns someone's lousy day into one that

feels lucky.

On his fifth day, in the middle of a fierce snowstorm, he

met Davie McInally, a Scottish man with icicles frozen in his thick beard

who was carrying his belongings in a backpack and trying to get to New York

to enlist in the military. McInally hoped to serve on active duty and earn

his citizenship, and the $10, added to his $14, made a bus ticket possible.

"I am sure there have been quite a few people now that those 10 dollars

have really helped, or made their life or even their days a lot better,"

McInally wrote in an e-mail.

- Georges Bataille, The

Accursed Share, Vol. I. Consumption (Zone Books, 1991). Most Anglo-American

readers know Bataille as a novelist. The Accursed Share provides an

excellent introduction to Bataille the philosopher. Here he uses his unique

economic theory as the basis for an incisive inquiry into the very nature

of civilization. Unlike conventional economic models based on notions of scarcity,

Bataille's theory develops the concept of excess: a civilization, he argues,

reveals its order most clearly in the treatment of its surplus energy. The

result is a brilliant blend of ethics, aesthetics, and cultural anthropology

that challenges both mainstream economics and ethnology.

Bataille’s “general

economy” in which the calculus of exchange givesway to a grandiose,

“solar” potlatch—a festival of sacrificialexuberance—prefigures

the turn of philosophy to writing, where all discursiverestraints are now

lifted and where the “gift” of being—Heidegger’s es

gibt—is now iterated as the word untethered. Bataille’s writing

is beyond writing to thepure mobility of the sign. Postmodernism is Bataille’s

gift. The theory of the “gift” which becomes so prominent in French

postmodernism from Derrida to Marion does not originatewith Heidegger. It

is seeded with Bataille. Bataille read closely Marcel Mauss’analysis

of the potlatch, of the sacrifice as donum gratiae, of the exuberance

of excessive giving which has no “economy” in the strict sense,

but which calls intoquestion all discourses and signifying economies. These

economies, with their logical and syntactical architectures, had to be “deconstructed.”

-

Michelle H. Richman,

Reading Georges Bataille: Beyond the Light (1982). Richman elucidates

the shift in from Marcel Mauss's notion of The Gift to Bataille's conception

of general economy and dépense.

-

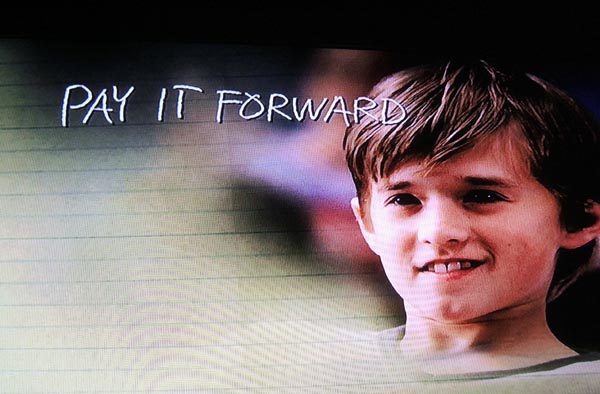

Catherine

Ryan Hyde, Pay It Forward (Pocket Books, 2000).

The

book Pay It Forward has been translated into twenty languages for publication

in more than thirty countries, and was chosen among the Best Books for Young Adults

2001 by the American Library Association. The mass market paperback was released

in October 2000 by Pocket Books and quickly became a national bestseller. Pay

It Forward the movie (Warner Brothers) is in release.Catherine Ryan Hyde is

founder and president of the

Pay It Forward Foundation. She donates a portion of her Pay It Forward

paperback royalties and Foundation-related speaking honoraria to support Foundation

activities.

-

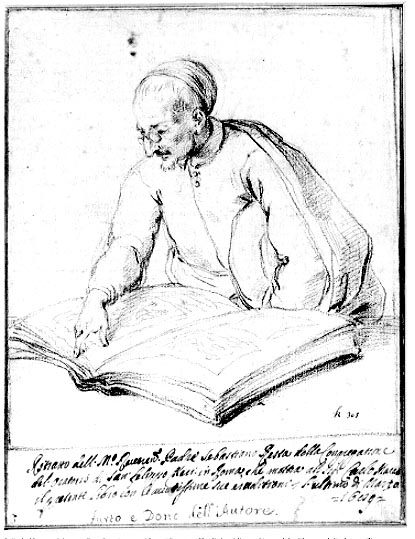

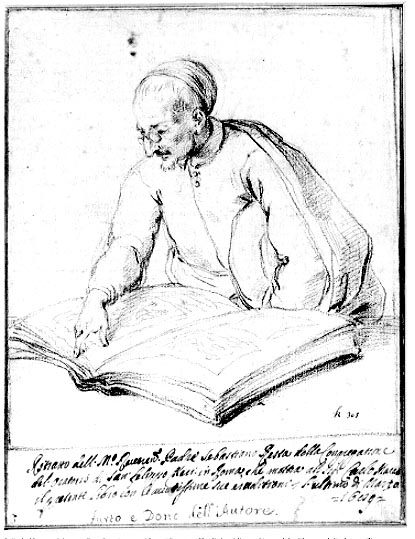

Genevieve

Warwick, "Gift Exchange and Art Collecting: Padre Sebastiano Resta's

Drawing Albums," in The Art Bulletin (December 1997): 630 -

646. This text examines gift exchange within art patronage by focusing on

Padre Resta (d. 1714), an Italian collector who "gifted" notable

figures with precious drawings, people who, in turn, gave monetary donations

to the Padre who gave the money to the poor through the auspices of a charitable

trust, an "Opera Pia." Warwick notes Resta viewed his gifting

as a double-movement, both theft and a gift (note the subtitle, in Resta's

own hand, in the sketch of Resta seen below, Furto e Dono dell'Autore,

"Theft and Gift of the Author"):

Carlo Maratta, Sebastiano Resta Examining an Album of Drawings

Warwick writes: "Resta

pondered the menace of the gift in describing the beauty and value of one

of his albums [of drawings destined to be given away]: 'I would give it

with pleasure to a friend, to gratify him with its beauty. And with pleasure

to an enemy, to avenge myself with its price."

-

Lucia

Travaini, Fragments and Coins: Production and Memory, Economy and Eternity,"

The Fragment: An Incomplete History, William Tronzo, ed. (Getty

Research Institute, Los Angeles, CA 2009). A hoard of late Roman and Byzantine

gold coins were discovered in 1586 in ruined ancient walls while digging

for the foundation of the new Palazzo del Laternao in Rome. Pope Sixtus

V, on December 1, 1587, issued the bull Laudamus viros gloriorosos (We

praise the glorious men) by which he blessed the Lateran Coins and granted

an indulgence to each of those 125 coins so discovered, making them all

relics; the Pope then distributed them gratis to emperors, kings,

princes, noblemen, cardinals, pious men, etc. so as to guarantee the new

owners spiritual benefits.

Solidus from the Rome Lateran Coin Hoard ( 1.5 in.dia., ca. 580)

-

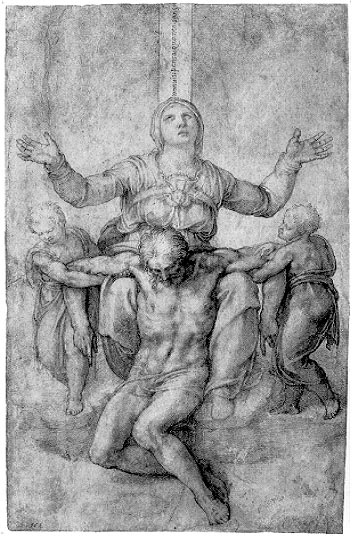

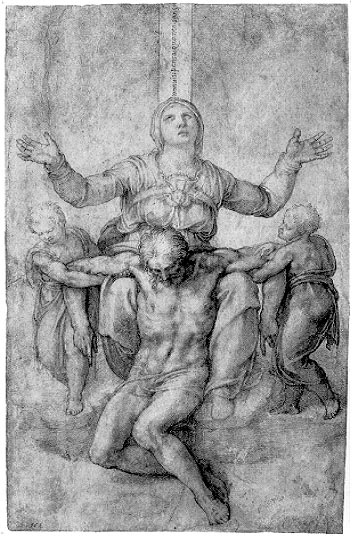

Alexander

Nagel, "Gifts for Michelangelo and Vittoria Colonna," in The

Art Bulletin (December 1997): 647 - 668. Nagel examines a drawing of

the Pieta that Michelangelo made for Vittoria Colonna which was offered

as a gift: "In this process the notion of the gift -- inherent both

in the drawing's subject, the sacrifice of Christ, and in the circumstances

of its making and presentation -- played a key role. For Michelangelo and

Vittoria Colonna, the drawing conceived as a gift was deliberately exempt

from the normal economy of art production in the period."

Michelangelo, Pieta for Vittoria Colonna

Jacques

Derrida, The Gift of Death (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995)

and Given Time: Counterfeit Money (Chicago: University of Chicago Press,

1992).

The

gift, according to Derrida, is "beyond recompense or retribution, beyond

economy," effecting a sort of sacrifice of economy itself (GD, 95).

The gist of Derrida's argument is: "The aporia that surrounds the gift revolves

around the paradoxical thought that a genuine gift cannot actually be understood

to be a gift. In his text, Given Time, Derrida suggests that the notion

of the gift contains an implicit demand that the genuine gift must reside outside

of the oppositional demands of giving and taking, and beyond any mere self-interest

or calculative reasoning (GT, 30). According to him, however, a gift is

also something that cannot appear as such (GD, 29), as it is destroyed

by anything that proposes equivalence or recompense, as well as by anything that

even proposes to know of, or acknowledge it. This may sound counter-intuitive,

but even a simple 'thank-you' for instance, which both acknowledges the presence

of a gift and also proposes some form of equivalence with that gift, can be seen

to annul the gift. By politely responding with a 'thank-you', there is often,

and perhaps even always, a presumption that because of this acknowledgement one

is no longer indebted to the other who has given, and that nothing more can be

expected of an individual who has so responded.

"Significantly, the

gift is hence drawn into the cycle of giving and taking, where a good deed must

be accompanied by a suitably just response. As the gift is associated with a command

to respond, it becomes an imposition for the receiver, and it even becomes an

opportunity to take for the 'giver', who might give just to receive the acknowledgement

from the other that they have in fact given. There are undoubtedly many other

examples of how the 'gift' can be deployed, and not necessarily deliberately,

to gain advantage. Of course, it might be objected that even if it is psychologically

difficult to give without also receiving (and in a manner that is tantamount to

taking) this does not in-itself constitute a refutation of the logic of genuine

giving. According to Derrida, however, his discussion does not amount merely to

an empirical or psychological claim about the difficulty of transcending an immature

and egocentric conception of giving. On the contrary, he wants to problematise

the very possibility of a giving that can be unequivocally disassociated from

receiving and taking." (Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy).

-

John

D. Caputo and Michael J. Scanlon, eds., God, The Gift, and Postmodernism

(Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999).

Professor Caputo specializes

in continental philosophy of religion, working on approaches to religion and

theology in the light of contemporary phenomenology, hermeneutics and deconstruction,

and also the presence in continental philosophy of radical religious and theological

motifs. He has special interests in the "religion without religion"

of Jacques Derrida; the "theological turn" taken in recent French

phenomenology (Jean-Luc Marion and others); the critique of onto-theology;

the question of post-modernism as "post-secularism;" the dialogue

of contemporary philosophy with St. Augustine; the recent interest shown by

philosophers in St. Paul; the link between Kierkegaard and deconstruction;

Heidegger's early theological writings on Paul and Augustine; "secular"

and "death of God" theology; medieval metaphysics and mysticism.

- Australian EJournal

of Theology (August 2004 # 3 - ISSN 1448 - 632); click on article title

to view Brian Johnstone's essay.

- Jean-Luc Marion, Being

Given: Toward a Phenomenology of Givenness (Palo Alto: Stanford University

Press, 2002).

Jean-Luc Marion is one

of several contemporary French philosophers who focus upon the issue of givenness

and gift; other notable French thinkers who have addressed this theme are

Jacques Derrida and the late Claude Bruaire.

- Lewis Hyde, The Gift:

Imagination and the Erotic Life of Property (New York: Vintage, 1983).

Twenty years ago, Lewis Hyde wrote a book called The Gift: Imagination

and the Erotic Life of Property. At first glance, some people might

have thought it was just a book of literary criticism, since it treated

the works of great American writers like Whitman. But The Gift was

really one of the most profound examinations of what it means to be an artist

in a capitalistic society ever written. Hyde’s discussion of how the

economics of scarcity can stunt the growth of creative people is, by itself,

worth the price of admission. The Gift is original thinking of a

high order.

Above all, Hyde

is interested in examining the effect our current immersion in the market

economy and the myth of the free market has both on our view of gifts and

on our ability to give and receive them. The market economy is deliberately

impersonal, but the whole purpose of the 'gift economy' is to establish

and strengthen the relationships between us, to connect us one to the other.

"It is this element of relationship which leads [Hyde] to speak of

gift exchange as 'erotic' commerce, opposing eros (the principle of attraction,

union, involvement which binds together) to logos (reason and logic in general,

the principle of differentiation in particular). A market economy is an

emanation of logos."

In many aspects this

is an exceptional book. It not only discusses the history of gift in culture

but through the work of Walt Whitman and Ezra Pound it discusses the gift

in poetry and art as well. The book focuses on the importance of gift, the

flow and movement of gift, and the impact that the modern market place has

had on the circle of gift. From the opening pages when Hyde amusingly discloses

the premise of gift by juxtaposing the Indian Giver with White Man Keeper,

the book progresses the gift through community, folktale and art. If you have

ever been dismayed by the modern or postmodern. If you have ever wanted to

make your money, cash out and leave the madness, you should read this book.

Not only does it give you hope, it may rejunvenate your idea of community.

- E. F. Schumacher, Small

is Beautiful (New York, NY: Harper Perennial, 1989).

E. F. Schumacher writes:

"The development of production and the acquisition of wealth have thus

become the highest goals of the modern world in relation to which all other

goals, no matter how much lip-service may still be paid to them, have come

to take second place. The highest goals require no justification; all secondary

goals have finally to justify themselves in terms of the service their attainment

renders to the attainment of the hightest."

- Maurice Godelier, The

Engima of the Gift (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999)

Maurice Godelier’s

career was to be deeply influenced by his encounter with the Baruya, a New

Guinea Highlands society discovered in 1951 by the Australians which has neither

classes nor a state structure, but which is characterized by a high degree

of gender inequality and numerous institutions serving male domination. He

observed and analyzed the transformations in this hunting-horticultural society

that very quickly entered the market economy, was integrated into a state

imposed by the West and exposed to the missionary zeal of Christian churches.

Alongside his field research, Maurice Godelier has explored a number of domains

essential for the development of the social sciences: reflections on the “mental”

components of social relationships, on the necessary distinction between the

imaginary and the symbolic, on the role of the body in the construction of

the social subject and, more recently, on the distinction between the things

one sells, the things one gives and the things that must be neither sold nor

given, but must be transmitted. He offers an astute critique of Mauss, while

building on Mauss's scholarship.

- Gloria Goodwin Raheja,

The Poison in the Gift: Ritual, Prestation, and the Dominant Caste in a

North Indian Village (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988)

.

.

The Poison in the

Gift is a detailed ethnography of gift-giving in a North Indian village

that powerfully demonstrates a new theoretical interpretation of caste.

- Annette Weiner, Inalienable

Possesions: The Paradox of Keepintg-whle-Giving (Berkeley: University

of Calilfornia Press, 1992).

Inalienable Possessions

tests anthropology's traditional assumptions about kinship, economics, power,

and gender in an exciting challenge to accepted theories of reciprocity

and marriage exchange. Focusing on Oceania societies from Polynesia to Papua

New Guinea and including Australian Aborigine groups, Annette Weiner investigates

the category of possessions that must not be given or, if they are circulated,

must return finally to the giver. Reciprocity, she says, is only the superficial

aspect of exchange, which overlays much more politically powerful strategies

of "keeping-while-giving."

The idea of keeping-while-giving

places women at the heart of the political process, however much that process

may vary in different societies, for women possess a wealth of their own

that gives them power. Power is intimately involved in cultural reproduction,

and Weiner describes the location of power in each society, showing how

the degree of control over the production and distribution of cloth wealth

coincides with women's rank and the development of hierarchy in the community.

Other inalienable possessions, whether material objects, landed property,

ancestral myths, or sacred knowledge, bestow social identity and rank as

well. Calling attention to their presence in Western history, Weiner points

out that her formulations are not limited to Oceania. The paradox of keeping-while-giving

is a concept certain to influence future developments in ethnography and

the theoretical study of gender and exchange.

- Clifton Cuthbert, Art

Colony (Lion Paperbacks, 2006) traces the consciousness-rasing of freshmen

art students as they become politically radicalized and drop painting in favor

of L.E. Don's conceptual, socially-meaningful, collaborative artwork.

- B. Joseph Pine II &

James H. Gilmore, The Experience Economy (Boston, MA: Harvard Business

Review Press, 1999) gives examples of how surprise gifitng can be used to

improve profits, an interesting corruption of the gifting process.

Philip Romano, founder of Fuddruckers' and eatZi's and an Italian restaurant

named Macaroni's, gave away free meals to every diner in the rerstaurant once

each month on a Monday or Tuesday, a random practice that remained unannounced

unitl a letter arrived at each table in place of the check, saying how awkward

it seemed to charge guests for a meal, so this one was free. In another instance,

a hotel occasionally placed a storage canister, the kind resembling a soda

can, in minibars so that a surprised guest would discover a roll of fifty

one-dollar bills inside with a note confirming that the guest may keep the

money, compliments of fthe host.

.

.