DeGrane's Index

Picture

Man

White man

The Man White Mother Fuckin' Press Man

Black Gang Lover

Spic Gang Lover

White Prisoner Lover

Straight Dude Looking for Something - Policeman

The Photo Man

The European

The Springfield Connection

A Fair Man

An O.K. Photographer

An Artist

Homes

Homey

Fuckin' Photographer

Homo

Fuckin' Camera Man

The Camera Man

Inmate Lover

The Police

R.S.: Cute Mother Fucker

Friend

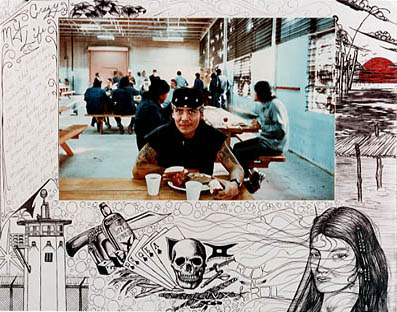

Saltzman first makes casual color

portraits of inmates and staff, then permits them to enframe their image with

a visual and verbal supplement that provides a frame (literal and textual)

through which one has to view the inmate's portrait. This metacommentary

provided by the subjects of the images examines the "position" of the inmates

within prison and within the discursive regime of the authorities and the

photographer who is representing them to us.

Keith

Baker, inmate from "La Pinta: Doing Time in Santa Fe"

(matte-finished

Cibachromes, pen and ink, 1982-83) by Robert Saltzman

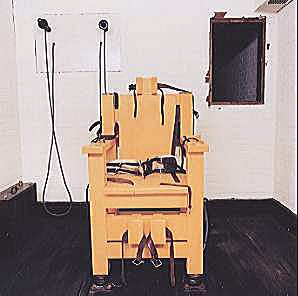

Devlin's unsettling color photographs

of the inhuman sterility of various execution chambers around the United States

depict no individuals, yet are more terrifying for it. The more anonymous

and banal these spaces appear to be, the more horrorifying. The space of state-sanctioned

murder (increasingly used today as states reinstate the death penalty) with

its bizarre instruments of death (gas chamber, electric chair, or lethal injection

tubes) is revealed with a knowing eye that makes us feel the revulsion toward

a judicial process that can so impersonally, in such institutional banality,

snuff out a human life.

Electric

Chair, Holman Unit, Atmore, Alabama,

"Omega

Series," Lucinda Devlin (1991)

Dedeaux, Finley, and Weber both use video to explore a dialogue between inside and outside, between free society and imprisonment. Finley, in her tape The Nomads at the 25 Door (1991) deconstructs the conventions of the usual talking head interview-with-the-inmate format of most prison documentaries. Her inmate-interlocutor behind bars turns the tables around and begins to interview Ms. Finley! The tape takes the viewer across the ocean to Yugoslavia and into the Bulgarian revolution before returning to the Nevada woman's prison and the young murderess and her "sisters" doing time there. In so doing, Finley problematizes the relationship between inside and outside, interviewer and interviewee, justice and injustice.

Dedeaux has facilitated a videotape

exchange between incarcerated gang-members and their counterparts outside

prison, a strategy to open the eyes of the outside members to the consequences

of their actions. Unfortunately, this tape and all of her taped material were

confiscated by the F.B.I. as evidence in a murder trial in New Orleans (involving

corrupt New Orleans police). Although the material was excluded by the presiding

judge, her tapes have yet to be returned, so Dedeaux has only provided the

following newsclipping documenting this incident:

New

Orleans newspaper clipping detailing Dedeaux's bout with the F.B.I.

Video artist Weber's tapes "Correcting Corrections, Part I: Crimes of Punishment" begins with a discussion of Adrian Lomax, an inmate in Green Bay, Wisconsin who was sentenced to three years in solitary confinement for writing newspaper articles for The Madison Edge, concerning the brutality of a certain prison guard and develops into a behind-the-scenes look at so-called "Corrections" in Wisconsin; and, "The CIA of State Government" (both 1993) concerning the death of an AIDS-infected inmate during restraint procedures at Waupun Prison in Wisconsin were produced in collaboration with prison activists Glen and Jackie Austin of WI CURE, Inc., a Wisconsin support group for the family of inmates. This strategy of collaboration synergistically unites the visually-educated artist with a politically-effective group to produce a consciousness-raising project more effective visually and politically than either could accomplish alone and present a model for some way artists with a social conscience can enrich and extend their artwork to a broader audience. For instance, these tapes have been aired on public-access TV and show by activist groups across the country, not just shown in an art context.

All these image-makers brush against the grain of how the prison inmate is frequently represented in our "law and order" society where he or she becomes merely "the con," the B-movie stereotype of the social reject who is unclean, over-tattooed, beyond rehabilitation. This Other constructed in the mugshot and the mass media, largely through the believability of photographic "evidence," and historically rooted in the pseudo-sciences of physiognomy and phrenology is the deviant from the social norm. He or she is often viewed as so deserving of punishment that even prison is considered too kind a fate execution is again seen as desirable punishment, as retribution.

This embodiment of negative,

antisocial attributes is produced, created largely in order to contrast

and, hence, distract the public from the abuse of "legitimate" crimes wrought

by the State and the Corporation: class bias, racism, structural unemployment,

destruction of the environment, white-collar crime and abuse of power,

militarism, and so forth. As the French thinker Jean Baudrillard put it:

". . . prisons are there to conceal the fact that it is the social in its

entirety, in its banal omnipresence, which is carceral." As this constructed

image of the "con" functions to representationally pigeonhole the lowest

social strata as perpetual threat, as a revolting social body in need of

perpetual discipline, it is hardly surprising that the image of "the con"

often reflects our racial fears, figuring this Other as either a person

of color, or as a projection of our own unresolved racial guilt as the

"white-trash" supremacist.

But why this stereotype? The stereotype of "the con" is useful. It provides a ready scapegoat; it embodies all that we fear and do not wish to see in ourselves. "The con" is the evil Mr. Hyde part of ourselves held firmly behind bars so that our benign Dr. Jekyll- self may have a clear conscience. Politicians, astute in public manipulation, have increasingly played upon such public fears, hyped up the stereotype in order to garner votes on a law and order platform, to promote reactionary politics and underwrite Calvinist religious Fundamentalism (there are only the Elect and the Damned), to sustain racism and an economy of economic injustice. The demagogues know how to milk the image of "the con" for all its worth. They know the prison inmate has suffered "civil death" and is relatively powerless (unless some outside benefactor speaks up) to alter the image. Using very different approaches, Camhi, DeGrane, Devlin, Firestone, Lyon, Finley, Saltzman, and Weber all challenge this stereotype and, hence, obliquely attack the neoconservative retour d'ordre which continues to use The Carceral Other as a political pawn.

Since this exhibition cannot possibly present an objective, totalizing per- spective on the Prison Experience, nor deal with the complex topic of the politics of prison, an integral part of this exhibition is the accompanying lecture series with its various presentations by individual activists be they inmates, former inmates, penologists, lawyers, ministers, or just people of conscience and the multifarious prisoner support groups active in the Chicagoland area. It is to these individuals and groups that this exhibition is dedicated.

James Hugunin, the curator of this exhibition, teaches the History of Photography and Contemporary Theory in the Department of Art History, Theory, and Criticism, The School, The Art Institute of Chicago.