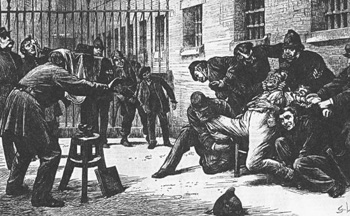

Policeman and his collared Captives (1870),

anonymous (collection of Stanley B. Burns, M.D.)

This exhibition—opening on the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Attica Prison Uprising — focuses mainly upon work by Morrie Camhi, Dawn Dedeaux, Lloyd DeGrane, Lucinda Devlin, Jeanne C. Finley, Robert Saltzman, and Marshall Weber. Historical balance is given by including Cinda Firestone's film documentary Attica (1971), preserved on video, and Danny Lyon's images from his photo-book Conversations with the Dead (1971), in addition to related historical items, such Richard Lawson's prints from glass-plate negatives in "The Joliet Prison Photographs 1890 - 1930" (1981).

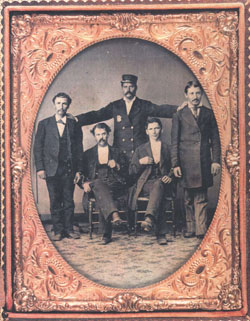

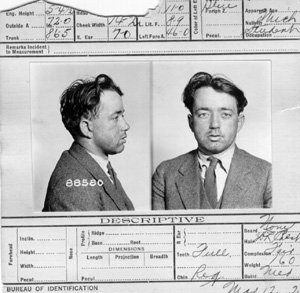

Mugshot, No. 7213 (c. 1915) from Richard Lawson's

"The Joliet Prison Photographs 1890 - 1930" (1981)The contemporary image-makers featured here each present a different strategy and perspective concerning The Prison Experience. Like the proverb about the Blind Men who each describes an elephant based upon touching one part of that large beast, these image-makers' representations, albeit sincere, are partial, imperfect constructions of the carceral. As diverse as their approaches are, their vision is still that of an outsider looking in, they are not In the Belly of the Beast as the title of inmate Jack Henry Abbott's boasts and as depicted in the imagery of inmate-photographers reproduced in the photo catalogue Photography from Within (1974) on display here — but neither is their vision merely naive.

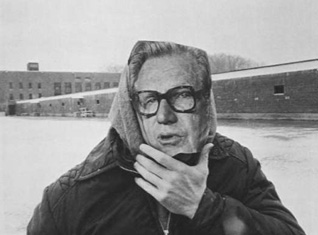

Nelson Rockefeller is put (symbolically) behind bars

(gelatin silver print, 1976) by Robert H. from the catalogue

Photography Within (The Floating Foundation of

Photography: New York, 1977)Even as their work "speaks up" for the inmate who is often denied an empowering visual representation, they subtly question the naive belief in the veracity of the photographic image and critique those who would knowingly or not perpetuate the stereotyped B-movie image of "the vicious con." Thus, the works in this show deal with the politics of representation; they point to, despite their outsider status and difference of approach, the ideological construction of the repressive image of "the con" for the con it is. Paradoxically, in so doing, their imagery overlooks the violent, chaotic conditions that obtain in maximum-security prisons. To photograph such would risk producing images that could be misread by the average viewer, those unfamiliar with the prison experience, as confirming the B-movie stereotype. Why? Because the source of that violence and chaos would mostly likely be perceived as originating wholly from the "corrupted natures" of the inmates, rather than seen as an innate structural aspect designed into such an institution. The infamous high-tech, high-security units where inmates are isolated in their cells most of the day are the latest, most "rationalized" attempt in this regard.

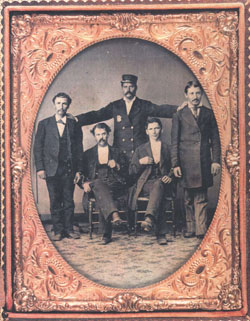

"An Unwilling Sitter for a Police Record,"

The Graphic (woodcut, 1873), Sir Luke Fildes

Furthermore, one must recall that these images were obtained only with the permission of the Prison Authorities; the limits of representation had already been laid down by the warden, as well as inflected by what the inmates themselves felt comfortable with the photographer seeing. Moreover, absent here are those high-security units — such as Marion Prison in Southern Illinois and the notorious Pelican Bay facility in North California — and "chain-gang" labor that are being increasingly employed as regressive punishments toward inmates (disproportionately people of color) who are increasingly being dehumanized in the popular media as monstrous Others deserving subhuman treatment.

Physiognomy and Phrenology—Pseudo-Sciences Using the European Caucasian as the norm of perfection, these supposed sciences of the cranium and the face claimed they could specify deviancy from that norm — either the genius or the idiot, the saint or the criminal — by a careful study of those physical features. These methods were also used to specify racial differences and reenforce racial stereotyping. The idea was to be able to read character by mapping the invisible mental/moral qualities onto the visible physical features of the subject. Photography was used to lend "objective visual data" to underwrite this supposed science in two ways:

1) specify individual peculiarities (the Bertillon Measurement mugshot system as developed in France by Alphonse Bertillon);

Bertillon Measurement Mugshot (1923), Chicago Police Department

2) reveal common characteristics among a group (of geniuses, mental defectives, criminals, etc.) by compositing (printing one image over another, over another, etc.) several identically posed mugshots until, supposedly, archetypal traits emerged and individual differences blurred out. This method was called the Galtonian Composite after its French inventor Frances Galton. The physical stereotype of "the con" rose to public awareness through these erroneous methods. Photography was used repressively to further these dubious studies. Hence, mugshots were not only a means of identifying specific criminals, but also a way to display the general criminal type that society was to identify and protect itself against.

The Deep Structure of the Carceral Narrative

In studying scores of articles, photographic books, inmates' writings, and so forth, I have discovered a common underlying structure to the stories being expressed, a mythic structure identical to what Structural linguist Jurij Lotman pointed out as underlying all folktales. This thesis developed in detail in my unpublished text which inspired this exhibition: Discipline and Photograph: The Prison Experience (1994). The plot-space is divided by a single boundary — an obstacle — such as the prison cell, wall, fence, or formidable gate. This obstacle produces two textual zones:

1) an internal sphere (the cellblock) and,

Two types of characters confront this obstacle:

2) an external sphere ("free" society).1) the mobile investigator (often a benefactor, such as Danny Lyon, Robert Saltzman, or the members of The Floating Foundation of Photography who taught expressive photography of New York State inmates) who enjoys freedom in regard to the carceral plot-space and mediates between inside and outside; and,

Their are, however, extraordinary instances where the inmates have been empowered — albeit through the efforts of a mobile individual who mediated between inside and outside the prison — to make their own images:

2) those who are immobile (the incarcerated inmates) who represent a function of that plot-space and can only overcome the obstacle (the civil death and invisibility that follows upon one's incarceration) with the assistance of the mobile investigator.1) Warden Percy Lainson of the Iowa State Penitentiary at Fort Madison permitted inmate-magazine staff-photographers in the 1950s to work freely within the walls;

2) The Floating Foundation of Photography's artist-photographers held in-prison photography courses, training the inmates (both men and women) to express their situation behind bars, helping them arrange an exhibition and catalogue of their work;

3) in Robert Saltzman's collaborative work with inmates at New Mexico State Penitentiary where this narrative dialectic of inside/outside is objectified, showing how his outsider's view becomes enframed and commented upon by the insider's response to his image and this carceral situation.