The twelve essays herein anthologized span six years, 1992-1987 and, to varying degrees, engage their critical objects within the context sketched in part one. One essay, "Meditations on an Ukrainian Easter Egg," was initially published in 1983, but substantially rewritten and expanded in 1991. All of the articles have been previously published except for the last three essays. All of the previously published essays have been revised from their original form: typos corrected, grammar smoothed out, and new material added in several instances. These additions were either reintroduction of material cut for the sake of brevity in the original, or wholly new thinking stimulated by re-reading the essay and/or by critical commentary on the original version. Although the most recently written of the essays anthologized herein — "Disputing Grounds" and "Discipline and Photograph: Agency/Structure and the Prison Experience" — have been placed at the end of the anthology. They function, along with this introduction, as "textual bookends" to the material in between, developing in a more theoretical fashion concepts implicit in the essays preceding. Thus, "Disputing . . ." discusses John Tagg's cultural theory, specifically his notion of the "mobile subject" and puts it in tension with Anthony Giddens's Theory of Structuration," the mutual implication of the stratified agent (composed of the unconscious, practical consciousness, and discursive consciousness) with structures (rules and resources that relate to the production of meaning the sanctioning of conduct) that both constrain and enable.I also place in contrast Tagg's nominalism, which does not permit him to allow for the various processes of "globalization" that have been examined by a wide range of sociologists, Giddens's thinking on how to mediate between the levels of the locale and the global by theorizing "the interrelation of locales and modes of regionalization with other properties of social systems.""Discipline and Photograph . . ." expands on Tagg's and Giddens's thinking vis-à-vis the "subject" as pertains to the agency/structure debate, situating it within the context of an analysis of the representation ("repressive," "honorific," and "appropriative") of prison and prisoners as found in two bookworks — Danny Lyon's Conversations with the Dead (1971) and Morrie Camhi's The Prison Experience (1989) — and two video tapes — Gary Glassman and Jonathan Borofsky's Prisoners (1985) and Stephen Roszell's Other Prisoners (1987). For instance, mugshots are repressive attempts at delimiting the identity of the person scrutinized, at freezing the mobile subject into immobility, while Lyon's humanistic attempt to redefine the repressed carceral subject in the personage of inmate Billy George McCune honors the persistence of agency in the face of massive structural constraint. Lyon's photobook is a paean to Parsonian voluntarism. Both Camhi's photobook and Roszell's tape, in contradistinction, assert a more complex interaction between agency and structure, a position more akin to Giddens's concept of the "duality of structures."

In my first essay, "Cultivating a Rhizome: Lou Stoumen's (Human) Family Album," this theoretical issue is broached in more concrete terms. Lou Stoumen (1917-1991) was an Oscar-winning documentary filmmaker and a maker of artist books who often recycled his documentary-style still photographs (from as far back as the 1930s up to the present) fashioning them into image-text combinations that he termed "paper movies." Somewhat akin to Marcel Proust's tome Time Regained, Stoumen's scripto-visual productions traffic in autobiographical memory, not merely for nostalgia's sake, but in order to deny the past its dead certainty (intractable, finished, gone); in the process, Stoumen plays both analyst and analysand. He revivifies photographs (what Roland Barthes called "the flat death") by textual fabulation. Not infre- quently, one photograph appears in different books with different (sometimes contradictory) captioning. Stoumen's epistemological assumption here is that of psychoanalytic inquiry where one is always dealing with versions of reality, a reality that is always mediated by narration.

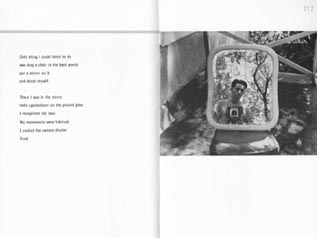

Page from Lou Stoumen's photobook

Can't Argue with Sunrise: A Paper Movie (1975)Far from being innocently encountered or discovered (as traditional documentary would have it), "reality" in Stoumen's books is produced in a regulated fashion. In these narratives, Stoumen, takes several roles: detached observer, hero, victim, dodger, friend, and lover. Any "unreliability," the varying accounts of events, must be understood as functioning in his narration as what psychoanalysts term "resistance." Thus, Stoumen seems at times to prevent himself, and us, from probing too deeply, from knowing too completely. At times, the declarative voice of the narrator often shifts into introspection, a mode of discourse that suggests that far from having primary control over our lives, we witness them. Stoumen, by recalling and reusing previously-made images, can simply witness his life, a posture that tends to soften personal responsibility. Hence, a duality is produced in Stoumen's narration: on the one hand, the active agent, the creating self; on the other, the passive self, looking introspectively at the web life has woven around him. Consequently, this catalogue essay addresses the inconsistencies, paradoxes, and lapses in Stoumen's work and personal life, attempting to read these as symptoms of the "duality of structure" represented by Stoumen's particular interventions (agency) in a potentially malleable object world (structure) that both constrains and enables him: aesthetically, professionally, and interpersonally. That is, even as Stoumen attempts to present himself as the quintessential originating subject producing unitary texts, his narratives produce him, in turn, as a mobile and stratified subject.

Professionally, recognition for Stoumen from mainstream photographic curators has been nil or guarded; critics, such as Andy Grundberg, were often hostile; feminists would find much to take issue with in his life and work; family members, often still feeling the sting of financial and emotional rejection or indifference, give the man mixed reviews (he married and divorced more than a few times); a file of letters from former lovers (yes, he kept every one!) consistently rage against the man's egotism, his need to control others, and his lust for fame; and yet . . . the man was undeterred from a task that would bind together his life in a new structure that defies simple ordering and linear progression. He cast a nonhierarchical network — a "rhizome," as Deleuze and Guattari call this acentered field of interconnections in their tome A Thousand Plateaus (1980) — across the dusty paths, precarious trails, hills and valleys, blind alleys, cul-de-sac's, busy streets, raceways, turn-abouts, and aerial flight paths that constituted his multifaceted life. He found his "paper movies" ideally suited to be narratological analogues for this acentered structure, so well did they encourage flows and lines of flight mirroring those of his own desire. In summary, my essay attempts to describe Stoumen as a productive, desiring agent — as a subject-in-process — who is mutually implicated in the structures of familial, social, and aesthetic interaction. This dialectical interaction, this duality, informs my attempt to trace Stoumen's mobile identity as it is produced within the discursive regime of this storyteller's shifting repertoire of imagery and words.

Maintaining an interest in the producing/produced subject, my second essay addresses twenty years of photographic-related work by New York artist Barbara Kasten. With few exceptions, her work is formalist and anti-narrative and is situated 180 degrees from Stoumen's. Whereas Stoumen uses form and architecture mainly to situate his divers characters within the dance of life and death, Kasten eschews flesh and blood actors. She prefers to heat up the cool geometry of objects and architectural sites via vibrant color and "retro-abstraction" that recalls the photographs made by Florence Henri in the late 1920s.

Construct PC/III-A (Polacolor ER

Land film, 1981) Barbara KastenMost recently, she exercises restraint in abstraction, preferring to accentuate and revel in the sublime mystery of uninhabited sacred spaces, such as New Mexico's Puyé Cliff Dwellings. By running these two essays consecutively, I suggest contrasting Stoumen's moralizing with Kasten's decorative hedonism — a comparison I find . . . interesting . . . particularly as each artist's work as been inflected by the Postmodern Turn. Kasten's most ambitious project — lighting and situating mirrors about major architectural sites and then photographing them, turning them into large color abstractions—comes under critical scrutiny in my discussion:

"The aesthetic ideal of the geometric ordering of space — in prisms, straight lines, and circles, the emphasis on the profile against the sky (as once espoused by Le Corbusier and other International Style architects) — is taken to a second-order (metacommentarial) level in Kasten's 'Architectural Sites' where it is both challenged and celebrated. The unifying discourse of architectural modernism is variously refracted as it filters through the artist's reflections on the history of forms. But one may argue that this style-scavenging vision, although it strives to achieve the ideal of universal beauty, actually reflects our compensatory attempts to cope with our worrisome experience of a decentering, post-industrial society steeped in simulation and suffering a legitimation crisis in its cultural, political, and economic spheres."

Kasten's "Architectural Sites" and her more recent transformations of the Puyé Cliff Dwellings seem to be aesthetic compensatory responses to a "Crisis of the Real" many feel to underlie our Postmodern Condition.