Recent writing by photo critic Andy Grundberg has taken up this issue, with the critic attempting to keep one foot in the "real" and the other edging toward the "hyperreal." "The Crisis of the Crisis of the Real," reviews photo critic Andy Grundberg's recently published anthology of essays. Again the emphasis is on a particular agent — a critic this time — but my discussion shades into an examination of the theoretical constraints and empowerment (intended and unintended) that Grundberg's thinking has woven, and how he understands the relationship between agency and structure. For instance, I observe:"Grundberg can move between two seemingly opposing poles, championing photography's more traditional idealistic accomplishments in relation to the individual (its ability to authenticate lived experience), as well as welcome some of its more radical materialist aspirations in relation to society (debunking the master discourses of the culture industry, de-naturalizing ideologies, hence, effecting social change). Grundberg's belief that 'this conflict, between tradition and the new, is . . . embedded in modernist art' confirms his critical tactics."

His text sketches out his "take" on our postmodern times and this permits me to develop, through engaging him on his issue, a context for the essays presented here. In his introduction, Grundberg desires to read photography encountered "in galleries, museums, and books" as "a form of art." At the same time, he claims his essays are informed by "ideas advanced by theorists like [Walter] Benjamin, Roland Barthes, and Jean Baudrillard," thinkers who have problematized the idealist notion of ART, blurring the boundaries between "art-making" and other material practices. He claims he will investigate photographs "as signs" and the medium "as a sign system much like language, but fundamentally different from it." Yet much of the criticism constellates around the individual creative artist (the agent) and his self-produced oeuvre, rather than focusing on abstract structures of meaning. Grundberg touts the agent, giving structure minimal attention. Although engaging with some sympathy postmodernist tendencies in photography, he tames this paradigm shift into merely a stylistic move analogous to the transition from Impressionism to Post-Impressionism. He appears unable to accept the fundamental questioning of the unitary subject, its replacement by the theoretical entity, the decentered subject; the corresponding problem of identity — an issue raised by contemporary theory's rethinking of the agency/structure dilemma — is weakly addressed.

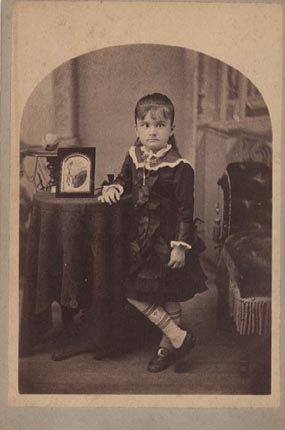

My fourth essay, "Meditations on an Ukrainian Easter Egg," (to see essay in its entirety, return to Writings listing and click on title) blurs the disciplinary boundary between the modernist antinomy: art (high culture)/populist imagery (material culture). The agent "behind" this image, one Andrew B. Paxton (1833 - 1902), was not a highly-trained, culturally-literate artist, but a conventional portrait photographer in small-town Albany, Oregon between 1859 and about 1900. Initially in the harness and saddle business, he turned to photography with a Mr. Thompson as partner; eventually, in 1868, Paxton bought his partner out, but later obtained another partner, Mr. Crawford, in 1884. His production — what of it I was able to trace in his hometown — was competent, but unremarkable, except for a rather singular cabinet card portrait (c. 1880) of one Winnoa Josephine Irvin (her name was scrawled in pen on the back of the card).

Winnoa Josephine Irvin (cabinet card, ca. 1880s)

by A.B. Paxton, Photographer and Artist, Albany, OR

This cross-eyed girl (suffering, in medical terms, internal strabismus) is dressed in her Easter best and stands — casually crossing one leg over the other as if to mimic her skewed gaze — near a marvelously decorated Ukrainian Easter Egg. Purchased for $1.50 in a small antique shop in Pearblossom, California in 1977, this card became an object for my Barthesian (à la Camera Lucida) musings. Winnoa's bifurcated gaze looked back at me until one day I attempted to set down my response to the image, to what art historian William E. Parker later effusively referred to as "the coded history of the soul." In my revision of this essay I tried to expand upon the implications of Parker's comments rather than wholly reject my earlier depth model of analysis; consequently, I researched further into the historical precedents as pertaining to imagery of the eye and embodiments of what Camille Paglia calls "sexual personae." This tact further shifts the emphasis from agency to structure, that is, to the internal formal relationships as well as to the external social context of this curious cabinet card, as well as broaching the imagery's psychosexual implications through a structuralist binary model:

"Winnoa Josephine Irvin has been rendered sexually ambiguous. What I've described as a structural tension between straight/skewed, and as a normative tension between perfect/flawed, becomes from a psychosexual perspective a sexual tension between male/female, a tension that may be resolved into the sexual persona of the androgyne. These aforementioned binaries — male/female; perfect/flawed; straight/skewed — succinctly abbreviate the ideology, if one privileges the first term over the second, of patriarchal dominance as given by Biblical Scriptures, Western philosophy, and Freudian psychoanalysis."